On the home front: Homeland Center residents did their part for the war effort

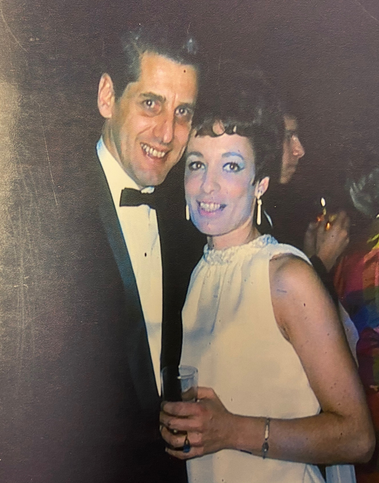

Lyn Russek (L) and Phyllis Duin (R)

All it took to reunite two childhood friends was a World War II-era photo and the Homeland Center newsletter.

As Memorial Day 2021 approaches, it is also a reminder that America’s veterans who once served in uniform were backed to the hilt by those doing their part at home – including Homeland residents.

The telephone reunion of Homeland resident Lyn Russek and her lifelong friend Phyllis Hammer came about Lyn was profiled for Homeland’s April 2021 newsletter. She mentioned that she had volunteered for the Navy League during World War II. Assigned to Abington Memorial Hospital, her duties included delivering meals to patients and filling tiny bags with sugar for their trays.

That sent the newsletter writer on an internet search, which revealed a digital version of Abington Memorial Hospital’s report on its work during the war years. On page five was a photo of two teenage girls in white uniforms. Could one of them be Lyn? Homeland Assistant Director of Development Ed Savage took an iPad to Lyn and showed her the photo.

“I was amazed, absolutely amazed that you could find something like that,” Lyn says. The picture showed her on the left and her friend, now Phyllis Duin, on the right.

Immediately, Lyn picked up the phone. She last talked to Phyllis more than five years ago, after Phyllis’ husband died. The last time they were together was at their 50th high school reunion in 1995.

“She picked up the phone right away,” Lyn says. “We had a wonderful chat. We talked over old times. It was wonderful to talk to her. We caught up on our kids.”

Lyn and Phyllis were close friends, part of a tight-knit group from elementary school. When World War II arrived, their mothers served on the Navy League, a civilian support group. It was a time when everyone chipped in to feel useful, so Lyn and Phyllis volunteered, too.

The work was hard, but Lyn didn’t mind. She took the bus to the hospital – her patriotic father gave up the family car to help conserve gasoline – and the girls had fun.

“If you haven’t lived through a war like that, it’s very hard to explain,” says Lyn today. “You’re very aware of everybody being needed, and you found something to do. My boyfriend in high school was a part of the air patrol. He went on patrol two or three nights a week and scoured the skies. We were young, but we did things. Everybody did something.”

When she was a bit older, Lyn joined a group of girls who helped host weekly dinners at the Philmont Country Club for patients from the local military hospital. When news came of V-J Day, Lyn got on the bus once more – free to all riders on this day – and went to the USO. It turns out that the classic image of overflowing affection to celebrate the war’s end was true.

“It was wonderful,” she says. “Everybody kissed everybody. Nobody knew who anybody was, but we didn’t care.”

While Lyn was filling sugar packets, another Homeland resident also did her part for home front health care. Lee Spitalny was a Girl Scout whose troop rolled bandages. They were gauze bandages, provided in rolls that the girls cut to prescribed lengths and rolled up for use somewhere in the world.

“At age 13, I was not that aware of the war, but my mother made sure I went every week and did the rolling of the bandages,” Lee recalls, adding that her uncle served in the Army but was never shipped overseas.

“I remember the mailman waving letters from my uncle as he walked down the street to deliver the mail,” Lee says. “It was like he was saying, ‘Guess what’s coming! Wonderful stuff!’”

Unlike Lyn, Lee was a bit too young to serve as a hostess for servicemen.

“I was 13, and I wanted to volunteer at the USO and dance with the soldiers, and my mother said, ‘Get in your bedroom, and you’re going to stay there,’” Lee recalls with a laugh. “She didn’t send me to my bedroom, but she explained, ‘Honey, no USO.’”

Even after retiring at age 72, Pat helped present story times at St. Stephen’s Episcopal School’s after-school program. Her husband died in 2013, and five months ago, Pat moved to Homeland. At Homeland, Pat reconnected with Pastor Dann Caldwell, who sang in the St. Stephen’s choir with her son when they were children and now provides spiritual counseling to the residents.

Even after retiring at age 72, Pat helped present story times at St. Stephen’s Episcopal School’s after-school program. Her husband died in 2013, and five months ago, Pat moved to Homeland. At Homeland, Pat reconnected with Pastor Dann Caldwell, who sang in the St. Stephen’s choir with her son when they were children and now provides spiritual counseling to the residents.